Rethinking the Electoral College

Note: Originally published by the author on The American Liberal blog.

The Electoral College has become a point of contention in the 2020 Democratic presidential primary debate, with several candidates calling for its repeal in favor of a national popular vote for the office of the presidency. This has spurred a renewed interest nationally in the Electoral College, its merits and demerits, and whether it should be scrapped, modified, or left alone. As one might expect, given recent electoral history, most of the support for repeal is coming primarily from Democrats and the left, with support for keeping the system as is coming from Republicans and the right. One might be tempted to write the whole disagreement off as bad-faith partisanship, but there are deeper philosophical questions at stake here, as well as conflicting interests that are not in themselves partisan. In order to decide this matter wisely as a nation, we must consider and evaluate the arguments adduced on both sides of the debate.

Before evaluating the various arguments for and against the Electoral College, it bears asking, “Just what is it?” One could write a treatise on its provenance and evolution throughout American history, but for the twin purposes of brevity and salience, we shall consider it primarily as currently constituted, with only brief mention of relevant historical factors.

The basic structure of the Electoral College is as follows: Each state is apportioned a number of electors equal to the combined number of representatives and senators from that state. How these spots are filled is determined by the laws of each respective state. These electors meet on a certain Monday in December following a November presidential election to vote for the offices of president and vice-president. It is their votes, rather than the national popular vote, which determines the outcome of a presidential election.

The founders originally intended that a state’s set of electors would be chosen by popular vote on a district by district basis. These electors would be non-partisan free-agents, who would meet and engage in a process of rational deliberation to select the most qualified and virtuous candidate. The people at large would not vote for presidential candidates directly, but would instead vote for these electors as intermediaries trusted to make a wise choice. This is manifestly not how the Electoral College functions today. The developments of distinct political parties, general ticket, and winner-take-all state rules have morphed it into something altogether different. As currently constituted, in 48 of the 50 states and DC, the people of a state vote for a presidential ticket, and the candidate winning the majority of the state’s popular vote receives all of the state’s electors. This is what is meant by statewide winner-take-all rules, and it makes the Electoral College effectively a weighted popular vote system, mediated through the states.

This system has many effects, but three are important to note here. One is that this system entails that individuals in the various states do not have equal voting power. Because the number of electors from a state is equal to its Congressional delegation, and each state has two senators and a minimum of one representative to the house regardless of population, an individual’s vote in a less populous state translates (assuming said individual votes for the winning candidate in that state) to a proportionally larger share of the effective electoral vote. The second consequence is that, due to the statewide winner-take-all rules, a good portion of voters in each state have no representation in the electoral vote count whatever. If 50.1% of a state’s voters vote for one candidate and 49.9% vote for a different candidate, the latter voting block will be unrepresented in the electoral vote tally. The third consequence is the fact that a candidate can lose the national popular vote, but win the Electoral College, and thus the presidency. This has happened four times in American history, in the elections of 1876, 1888, 2000, and 2016.

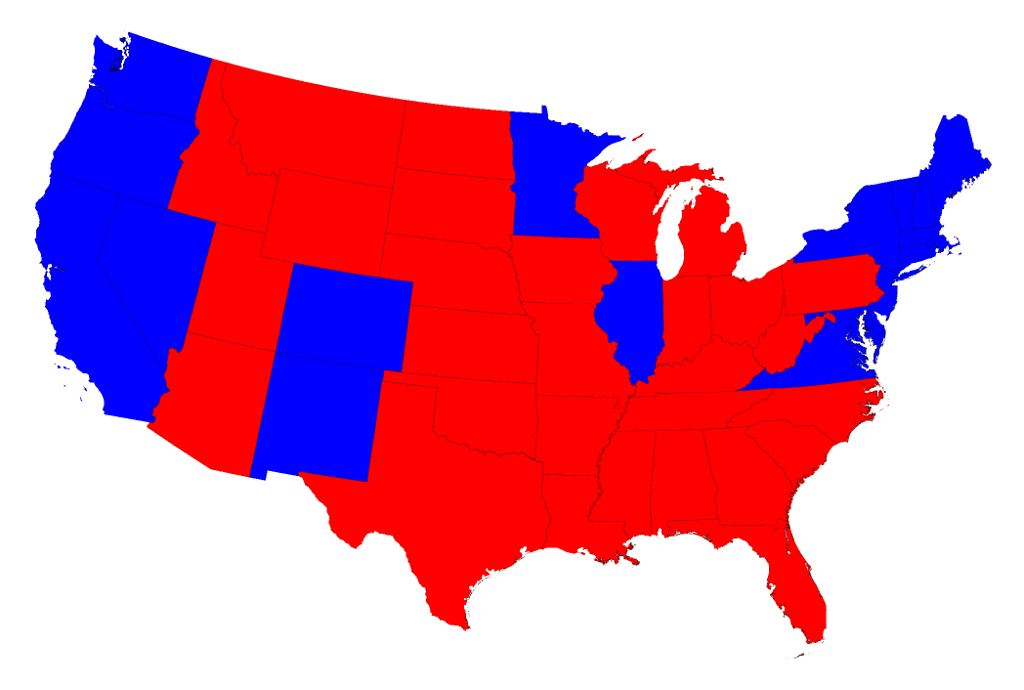

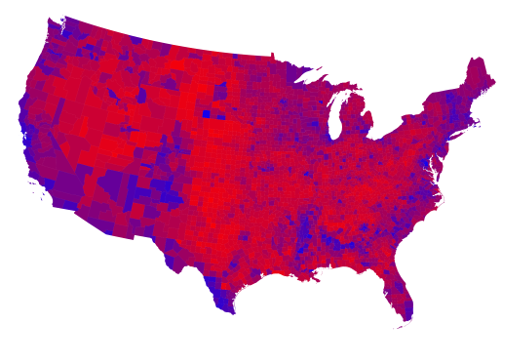

The statewide winner-take-all nature of the present system has the effect of skewing political perception and discourse, leading to talk of “red” and “blue” states and hiding the diversity of opinion within states, when each state is more realistically considered as some shade of purple. It also creates a situation where only a handful of competitive “swing states” are relevant to the outcome of an election. More on this later. To illustrate the effects of the winner-take-all system on the way we perceive the political alignment of the country, consider the contrast between the standard Electoral College map and the following one, which colors each county on a gradient between red and blue based on vote percentages within each:

One of the chief objections to the Electoral College is that it runs counter to the philosophical and legal principle of “one person one vote.” As mentioned, individual citizens in different states have unequal representation in the Electoral College, while those in minority voting blocks within each state are completely unrepresented. It violates two fundamental principles of democratic-republican government, representation and equality among citizens.

Another objection that may be levied against the Electoral College is that it does not actually answer to its original purpose and justification, and may in fact have effects contrary to the intentions underlying its initial conception. As originally conceived, the Electoral College’s deliberative process was to insulate the presidency from the whims of populism, preventing the election of an unqualified, incompetent, demagogic, or tyrannical individual to the highest office in the land. Many of the framers feared that popular election might lead to these outcomes, and so devised a system whereby these rational deliberators sit between the populace and the presidency. The current system, however, features no deliberative process, being a state-based popular vote, privileging voters in certain states more than others.

The foregoing fact is, interestingly, often adduced on both sides of the debate. As part of this critique, however, it leads us to the question of what kind of voters are disproportionately privileged by this weighting of different states. Rural, Southern states have electoral power which outstrips their population size. This comes as no surprise to the historian of American governance, who will remember that it was the Electoral College, as well as the Three-Fifths Compromise, which gave the slaveowning South its outsized political power. Slavery was abolished, Jim Crow defeated, but voting majorities in many of these more rural states are still privileged in the Electoral College over the majorities of many other states. One can wonder what effect this may have on the likelihood of electing someone the likes of whom the Electoral College is ostensibly intended to guard against. The though occurs that, if hedging against the tyranny of the majority is the object, perhaps a system that electorally privileges majorities in states which have long documented histories of popular majoritarian tyrannies against minorities might not be the best way to achieve that end.

Moving now to arguments in its favor, we must consider the flip side of this geographical privileging. Proponents of the Electoral College argue that instituting a national popular vote would lead to a situation in which candidates would be incentivized to campaign only in urban population centers, neglecting rural or less populous areas. As a consequence, the interests of these less densely populated areas would fall by the wayside. This concern is often bundled in with broader concerns about the role of federalism in the electoral system, and one sometimes hears this argument couched in talk about rural states vs. urban states’ interests.

First, as a response to this concern, it is not well established that a national popular vote would lead to candidates campaigning only in urban areas, given that it would incentivize generating as many votes as possible, and a sizeable portion of Americans live in rural areas. This concern is largely speculative. Second, we can observe that the current system already incentivizes campaigning only in a very small handful of swing-states, to the exclusion of all others, rural or urban. Whatever the effect a national popular vote may have on campaigning, it could hardly be as exclusionary as the current incentive structure.

Concerns regarding federalism underlie many of the defenses of the Electoral College system, so it’s worth discussing in more depth. Federalism, the distribution of powers between state and the federal governments, has been an integral feature in the makeup of our republic, alongside certain other features such as representative democracy, separation of powers among the tripartite branches, constitutionally enumerated rights, and the independence of the judiciary. Our government is a blend of different and sometimes contraposed elements, intended to distribute power and balance one another so as to protect the rights of individuals, and to promote the unity and longevity of our republic. One can think of the current debate in large part as one of the proper balance between the federalism element and the representative democracy element within our system of government. Both are important to consider, but which element is more relevant here, with respect to the relationship between the individual citizen and the presidency? Which element, in this context, tends more to protect the rights of individual citizens?

Important as it is, there are those who emphasize the role of federalism to a point such that they seemingly forget that it is a means to an end rather than an end in itself, and begin to talk in ways which are philosophically suspect. One hears talk of “states’ rights,” “states’ opinions,” and “states’ interests,” as if states were more than mere nominal objects. Without veering too far into metaphysics, we must note that states aren’t the kind of things that have the capacities of experience and thought, and thus the kind of things that can properly be considered to have rights or opinions or interests of their own accord. It is rather the individuals who live in a state who properly have such things as opinions, rights, and interests. Whatever talk about “interests of a state” means, it must ultimately reduce to interests of the individuals within the state in order to be coherent talk.

With that said, individuals within states do not vote as a single block, but are split percentage-wise. In so called “red states” there are significant “blue” minorities, and in “blue states,” significant “red” minorities. Under the current system, these minorities votes are electorally ineffectual. One must presume that these voters have just as much civic concern for the interests of other people in their states as do those voting with the majorities in those states. Interestingly, the same sort of concern that a rural minority might have its interests neglected in a national popular vote ought to apply equally to the voting minorities within these rural states who are completely voiceless under the current system.

Several factors are important to gleaning the proper relationship between the individual citizen and the presidency, and speak against the concern that a national popular vote would significantly differentially advantage the interests of some voters over others along state-wise divisions. One is that the primary areas of governance in which a president has greatest power to effect change are regarding issues of broad national or ideological concern rather than issues that bear upon voters’ state level interests. Two, whatever contribution one’s state of residency makes to his or her choice of president, one’s ideology makes a far larger contribution. Liberals in Alabama share more interests in common, in terms of electoral preference, with liberals in California, than they do with conservatives in Alabama. The same goes for conservatives in both states. So why be more concerned about the potential to unequally favor voter interests along geographical lines, which makes a relatively small contribution to their voting interests, than the real and current absolute disenfranchisement of vast swaths of voters along ideological lines, which make a far larger contribution to their voting interests?

At this point, the defender of the Electoral College has a rejoinder. The reason geographical interests should take precedence is to prevent regionalism among parties that could lead ultimately to the dissolution of the union. It is not an empty concern, though it is also arguable that regionalism is equally or more likely under the present system. There are regional paths to the presidency within the Electoral College system. Indeed, it is noteworthy that the secession of the southern states leading to the nation’s bloodiest war occurred under the Electoral College. Furthermore, as an empirical fact illustrated by the purple county map above, both major parties have ideological penetration across the nation, and partisan geographical differences are differences in degree rather than in kind. The concern about partisan regionalism seems far more well-placed in a pre-industrial, pre-information age than today, when cultural, social, and political groups are becoming more and more geographically decentralized.

So where does this discussion leave us? The considerations regarding lack of representation under the Electoral College as it currently exists, the disenfranchisement of large numbers of voters within states, the inequality of individual voters across states, and the swing-state phenomena which disincentivizes campaigning in much of America speaks to the need for reform. Worries about the role of federalism in preventing regionalism and urban domination, while not established empirically, are still legitimate concerns.

There are many ways one could go about reforming the Electoral College. Perhaps the simplest type of reform is to replace the Electoral College with a simple national popular vote. Several measures have been proposed for reforming the Electoral College, some requiring a constitutional amendment, and others (arguably) achievable through such means as interstate compacts. Proposals have been advanced in Congress introducing constitutional amendments to institute a national popular vote, but have all fallen short of the two-thirds majority in both houses of Congress needed to pass the amendment to the state legislatures for ratification.

A newer proposal, the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact, hopes to achieve the same end without the need of a constitutional amendment. In the compact, states would allocate all their electors to the candidate winning the national popular vote, rather than the statewide popular vote. To date, fifteen states and DC have signed on to the compact, making up 196 of the 270 needed to win a presidential election. The compact is written so as to go into effect only after enough states have joined to make 270 votes, thereby turning the country into a de facto national popular vote system. Notably, this proposal implements a national popular vote while retaining the framework of the Electoral College, by using the plenary power granted to the states by Article 2, Section 1 of the U.S. Constitution to choose the manner in which electors are appointed. The compact is likely to face legal challenges under the constitution’s Compact Clause requiring Congressional consent for states to enter into agreements and compacts with each other, but it may nonetheless be more easily achieved than a constitutional amendment.

Aside from instituting a simple national popular vote, numerous other possibilities are conceivable. One such possibility involves states allocating electors by districts, either by Congressional Districts or specialized Electoral Districts. The primary impediment to this sort of reform is partisan gerrymandering, which has just been upheld by the Supreme Court. Without Congressional action to ban gerrymandering, any gains in representation would likely be offset by these gerrymandered districts. Partisan gerrymandering would also likely become even worse by joining it to presidential politics. A simpler, fairer system along similar lines is to have states allocate electors proportionally to the various candidates, according to the statewide vote, based on a uniform mathematical formula. Both of these ideas seek to make the Electoral College more representative of the voters within states, eliminating statewide winner-take-all, and thus removing the disenfranchisement of minority voting blocks within states. Unlike the national popular vote, however, they do not go so far as to make all voters equal in voting power. It can be seen as a compromise between those concerned with the one-person-one-vote principle and those concerned with the urban-rural balance of power, as it still retains the current allocation of a number of electors per state which is not directly proportional to each respective state’s population.

Another interesting idea which would enfranchise all voters, institute one-person-one-vote, and also protect against regionalism is to institute a national popular vote with certain conditions. One could stipulate that to win a candidate must win the national popular vote as well as the statewide popular vote in a minimum number of states, or have a minimum percentage support in a certain number of states. The details would have to be fleshed out, but in principle, such a system would possess most of the best features of both the national popular vote and the current system.

No reform is likely to please everyone, and none will be free of negative as well as positive consequences, but one must weigh these consequences and decide which sort of reform stands to best achieve the ends we desire as citizens, that is, to further our individual liberties, make our system more representative, and foster the long-term stability of the republic.