Trump, the King of Fools

Far too much has been said already. Too much ink spilled. Too much bandwidth used. Too much oxygen burned. Too much mental energy expended. Too much opportunity cost spent. Too much time wasted of the brief lives of mortals in arguing the painfully obvious, only to have such uranium-clad reasoning fail to move the slobbering mass of imbeciles who still support him, and who are still numerous enough within the electorate to threaten the world and the republic with a second disastrous term of Donald Trump. That so many people in what appears to be a persistent vegetative state are capable of walking upright to the polls is quite an astounding fact indeed, and one that must be reckoned with.

Far too much has been said already. Too much ink spilled. Too much bandwidth used. Too much oxygen burned. Too much mental energy expended. Too much opportunity cost spent. Too much time wasted of the brief lives of mortals in arguing the painfully obvious, only to have such uranium-clad reasoning fail to move the slobbering mass of imbeciles who still support him, and who are still numerous enough within the electorate to threaten the world and the republic with a second disastrous term of Donald Trump. That so many people in what appears to be a persistent vegetative state are capable of walking upright to the polls is quite an astounding fact indeed, and one that must be reckoned with.

Trump is truly sui generis in the annals of American politics. Among political figures, historical and contemporary, he is uniquely stupid, inarticulate, and unlettered. He is malignant narcissism incarnate, with no sign that he possesses anything resembling common human empathy or decency. He is comically arrogant and oblivious to his own many shortcomings, both moral and physical. He often cruelly criticizes the looks of others, while himself looking something like a pear-shaped, orange, saggy sack of flesh in an ill-fitting, gauche suit and tie, topped with a combover that continues to mystify origami aficionados the world over. He has no scruples against projection, hypocrisy, and intellectual dishonesty of all kinds. He is constitutionally incapable of emotional equanimity or anything like stoic reserve. He is a sore loser. He is a sore winner.

He is the only president in history to have been criminally indicted, facing ninety-one felony charges. The only president to have been impeached twice. He has the ignominious honor of having had the highest staff turnover in presidential history and an unprecedented number of former cabinet members, including the usually apolitical military brass, speak out against him, both during and after the national clusterfuck (a technical term) that was his presidential term. This large list of detractors includes his attorney general, secretary of state, multiple chiefs of staff, multiple secretaries of defense, multiple national security advisors, numerous aides of all sorts, and his own vice president. The man has more disgruntled ex-lawyers than Wilt Chamberlain has ex-lovers. By a long shot, he is the most civilly litigated against, trailing a list of lawsuits numbering in the thousands. Twenty-six women have credibly accused him of rape or sexual assault, and a civil jury has found him liable for the sexual assault of one woman so far, making him preeminent among politicians for sexual misconduct—no easy feat.

He is the Old Faithful of liars, with deceptions both grand and petty regularly flowing from the fount of his oddly-shapen mouth like water from an ever-welling underground spring. He is paradoxically the world’s most obvious con man and perhaps its most successful one. A friend to dictators and enemies of the free world across the globe who browbeats and berates democratic allies. A draft dodger who disparages prisoners of war and fallen soldiers as “losers and suckers.” The only president who has ever whipped up a violent mob against both Congress and his own vice president. The only president to have been charged with conspiracy to defraud the United States, and conspiracy to deny citizens the right to vote and to have their votes counted. Need we go on? That this litany could be extended quite further is itself a crucially telling fact. Trump's unfitness for office is the most overdetermined conclusion in American political history. If it were any more overdetermined, it would be a tautology.

Despite all this, and despite the bleeding wounds of a scarcely countable and ever-growing number of both criminal and civil court cases, in both federal and state courts, involving election interference, fraud, mishandling of top-secret documents, hush-money payments to porn stars, defamation of his sexual assault victim, and others, he is still walking freely towards the GOP nomination. He is the real world analogue of the comically impervious horror-film villain who, despite sustaining stabs, blows, and shots that would have killed mortal men five times over, comes back again and again to rain havoc on the hapless protagonists. Behind this horror-villain stand the zombified droves of his supporters, as impervious to reason and common sense as he has hitherto been to justice. Continual efforts have been made to reason with them, but a steady plurality of the Republican base remains firmly inoculated against the ingress of manifest reality. Perhaps Thomas Paine, writing about a very different American crisis, said it best:

“To argue with a man who has renounced the use and authority of reason, and whose philosophy consists in holding humanity in contempt, is like administering medicine to the dead.”

Where reason cannot penetrate, perhaps ridicule is warranted. If the foregoing fractional sample of all the oh-so-evident reasons Trump is not merely unqualified for office, but supremely anti-qualified, is not enough to sway the voters in his thrall, then let them be both scorned and pitied for being fool enough to fall for Trump’s obvious lies and transparent con artistry. For it is not those of us who see him for what he is who are the targets of his deceptions. It is the most gullible of the gullible—his followers. A person could withstand being considered deplorable, and perhaps even take some twisted sense of pride in it, a sort of negative virtue signaling. Absolutely no one, however, wants to be revealed as an easy mark, a pawn, a rube, an idiot. The thing is—that’s exactly what they are.

On Rationality, Correctness, and Expertise

The confusion between rational justification and truth or correctness is common enough in public discourse that it need be noted that beliefs that are rationally justified sometimes turn out untrue, and beliefs without rational justification occasionally turn out to be true. Similarly, the most rational decision is not guaranteed to be the correct decision, and not all decisions that turn out to have been correct were rational decisions. Where this confusion becomes most pernicious is when members of the public run afoul of it when determining what to believe and in whom to place their trust.

The confusion between rational justification and truth or correctness is common enough in public discourse that it need be noted that beliefs that are rationally justified sometimes turn out untrue, and beliefs without rational justification occasionally turn out to be true. Similarly, the most rational decision is not guaranteed to be the correct decision, and not all decisions that turn out to have been correct were rational decisions. Where this confusion becomes most pernicious is when members of the public run afoul of it when determining what to believe and in whom to place their trust. Take a case wherein we have a preponderance of scientific opinion in favor of the truth of a certain claim X, but there are some outliers who take the heterodox view that X is false. In the fullness of time, X turns out false. In situations such as this, many people are apt, with the bias of hindsight, to imagine that this shows that the heterodox opinion was the most rational, and that those who held it the better judges of truth. In both respects, this line of argument is mistaken.

To truly determine the rationality of a claim, one must examine the quality and weight of the arguments and evidence for and against it in order to reach some idea of the probability of its being true. Likewise, to determine the quality of the judgement of those who make a given claim, one must also examine the evidence and arguments they proffer in support of the claim. Suppose that, according to sound reasoning on the basis of the best evidence available at the time, the probability of X being true was somewhere in the neighborhood of 80%. There’s still a roughly 20% chance that X will turn out false. One can hold the most probable belief on the basis of the most sound reasoning and highest quality evidence and still turn out to be wrong. On the other hand, one can hold the least probable belief on the basis of poor reasoning, based upon slim or no evidence, and nonetheless turn out to be right. That’s how probability works, contra certainty. Scientific work involves calculations of error and degrees of confidence, and are always subject to potential falsification in the future by more or better data. The rational belief to hold is the one that, at the time, is more probable given the best available evidence. The fact that people who bet on the improbable will sometimes turn out, in hindsight, to have been right is not a vindication of their rationality or judgement.

We have heard that a broken clock is right twice a day, but that doesn’t mean one should trust a broken clock as a generally reliable source of time. The judgement of those whose beliefs or decisions turned out to be correct, even in salient cases where much was at stake, should not be held in esteem merely on the basis of the correctness of their belief or decision in a particular instance. Rather, their judgement should be evaluated based on the rationality of the decisions or beliefs in question. By this metric alone can we ultimately establish the likelihood of sound judgement going forward.

One problem we face, when it comes to claims of interest to the general public that reside within special sciences or otherwise highly technical or specialized fields, is that members of the general public, or even experts within unrelated fields, are often not equipped to evaluate such highly technical or specialized evidence and argumentation. Even if, given enough time and effort, a person could amass the proficiency and knowledge needed to evaluate claims in a particular specialized field, this process would be prohibitively time-consuming if attempted for all domains of importance in making decisions in personal and political life. Given this, where one cannot evaluate claims directly, one must ultimately rely upon trust in the testimony of others who are experts within the relevant specialty. But how does one rationally determine in whom to place this trust?

The various methods of evaluating in which expert opinions to place ones trust are somewhat less well defined than those for evaluating claims directly, but there are analogous features, and they ultimately result in a similar assessment of probability. One might start by noting that an opinion held by one expert in the relevant domain is generally more reliable than one held by a non-expert, an opinion held by multiple experts yet more reliable, and an opinion held by a majority of experts more reliable still. Other factors also bear upon reliability of the expert opinion. Is the opinion held by a body or organization of experts that has objective standards, methods, and procedures that serve as both a rational process of arriving at truth, and as checks and balances to keep the experts honest? These features would include such things as methodological standards of scientific inquiry, judicial standards of evidence, competition between different opinions or adversarial processes, peer review, codes of ethics, etc. These and other similar factors jointly contribute to bolster the reliability of expert opinion.

Despite this, just as the most probable claims can nonetheless turn out to be false, the most reliable expert opinions can sometimes turn out to be wrong. Additionally, the most reliable expert opinions sometimes turn out to be spectacularly wrong on issues which are of great importance and consequence. Does this mean that these experts should not be trusted, or that other experts who don’t have the hallmarks of reliability previously mentioned, but who happened to be right on some salient issue, should be trusted over those who do? No, for the same reason advanced above in the case of the probability of claims themselves. That the more reliable expert opinion sometimes turns out wrong and the less reliable opinion sometimes turns out to be right is not an argument for the rationality of choosing the less reliable expert opinion. The important question is not whether the best available expert opinion will never turn out to be wrong. The important question is whether it is the most generally reliable source of truth amongst all necessarily imperfect sources. In consistently accepting the most reliable expert opinions, one will not always turn out to be correct, but one will turn out to be correct more often than if one does not consistently accept them.

The search for truth and the process of critical decision making are both inherently imperfect tasks that involve imperfect reasoners working from imperfect and incomplete experimental and observational data. Given this, the best that can be done to navigate these sometimes dangerous waters is to hold to what is most probable given sound reasoning from the best available evidence, or in cases where specialized expertise is needed, hold to what is likely the most reliable expert opinion given the sorts of objective considerations previously mentioned. The more this is put into practice, the more rational our worldview will be, and the better our decisions, both individually and collectively.

Liberalism: What it is and Why it Matters

Liberalism has often been considered the most successful political ideology in modern history, coinciding with vast and measurable improvements in human welfare, but recently new threats have arisen in the form of various anti-liberal populist and nationalist movements, which have gained some notable victories in liberal democracies in Europe and America. At the same time, some who self-apply the label ‘liberal’ have at times advocated decidedly illiberal ideas and policies, making the job of those who would defend liberalism from its critics that much more onerous. In the wake of these upheavals, we liberals must cogently recapitulate the core principles of our philosophy and contextualize its role in contemporary society in order to defend it both from the external and internal challenges it faces.

Note: The following has been adapted from an original post by the author on The American Liberal

Liberalism has often been considered the most successful political ideology in modern history, coinciding with vast and measurable improvements in human welfare, but recently new threats have arisen in the form of various anti-liberal populist and nationalist movements, which have gained some notable victories in liberal democracies in Europe and America. At the same time, some who self-apply the label ‘liberal’ have at times advocated decidedly illiberal ideas and policies, making the job of those who would defend liberalism from its critics that much more onerous. In the wake of these upheavals, we liberals must cogently recapitulate the core principles of our philosophy and contextualize its role in contemporary society in order to defend it both from the external and internal challenges it faces.

First, just what do we mean by ‘liberalism?’ It should be noted that what we mean here is not identical with the more narrow colloquial use of the term common in America, often referring to anything that happens to be advanced by the Democratic party, or a different but similarly constrained usage prevalent elsewhere in the world referring to a more conservative take on market economics. Liberalism is considered here as a broader, more comprehensive philosophy of government from which both of these more narrow traditions sometimes borrow.

Liberal philosophy has its roots in the Age of Enlightenment, but has precedents reaching as far back as ancient Athens. As with many broad ideological categories, liberalism is not so much a single philosophy as it is a family of philosophies united by their possession of some number of shared principles. Liberal philosophers have given different accounts of these principles and come to divergent conclusions about their particular implications. It would hardly be possible to do justice to them all. As our aim is not historical study but defending the liberal tradition, I shall simply try to articulate a broad, non-rigorous bird’s-eye-view conception of liberalism worth defending today.

One of the most central and foundational principles of liberalism involves a general consideration from moral philosophy about what sorts of things matter ethically. Liberalism takes the individual to be the primary object of moral concern. This is not to be confused with egoism or opposition to community and collective action. What is meant here is that what ultimately matters is the good of individuals—those autonomous, sentient beings who have the capacity to experience happiness or suffering, rather than such alternative candidates for moral ends as “The good of the party,” “The will of the king,” “The faith,” “The race,” etc. Liberalism takes as a fundamental principle that the greatest moral good is the flourishing, well-being, or happiness of sentient individuals, and that just political systems are established to further this end.

Next, we come to the namesake of liberalism. Liberalism holds that liberty is necessary for, or at least strongly conducive to, the individual’s achievement of happiness. Just as happiness or well-being is the primary moral good, freedom is the primary political good. Any political system calculated to improve the flourishing of its citizens must secure the freedom of individuals to pursue their own happiness. This principle is immortally enshrined in the American Declaration of Independence, in the phrase, “inalienable rights…life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.”

From this very general principle, many particular consequences follow, though exactly which liberties count as legitimate or important is a subject of dispute. Liberal societies have enshrined various freedoms into their constitutions and political cultures, but a few are largely agreed upon, such as freedom of expression, freedom of the press, freedom to vote for one’s leaders, freedom to own property and to engage in commerce.

Of these, the freedom of expression is perhaps the most fundamental. It was considered of such great importance by the liberal philosopher John Stuart Mill that he wrote, “If all mankind minus one were of one opinion, and only one person were of the contrary opinion, mankind would be no more justified in silencing that one person than he, if he had the power, would be justified in silencing mankind.”

Free expression holds the place it does in liberal philosophy precisely because it creates the framework wherein debate can occur from which truth can be uncovered and by which other freedoms may be argued for and gained. It was this particular feature that Martin Luther King extolled in his “Mountaintop” speech calling for America to live up to her promises when he said, “Somewhere I read that the greatness of America is the right to protest for rights.” Despite the brutal violations of this right by Bull Connor and others, its existence as a norm enshrined in the constitution and in the body politic allowed for King to make this argument, to organize, and to march on Washington in protest. Likewise, the success of numerous other reform movements has been predicated upon the right to freedom of expression.

Notions of equality are also central to the liberal project. Though individuals differ in myriad ways, in natural endowment of abilities, in wealth, ethnicity, or circumstances of birth, we are all alike in the way that matters most, our ability to experience happiness or flourishing on the one hand and suffering on the other. All have an equal stake in the achievement of happiness, thus all ought to possess equal rights under the law and equal access to public opportunities.

The principle of secularism, or separation of state and religion holds an important place in liberal government as well. Government should not impede the private practice of religion, nor should religious dogma impede the public practice of good governance. Reason and empirical science form the basis for good government policy capable of bettering the welfare of citizens.

Another important feature of liberalism is skepticism. Knowledge of the fallibility of human reason entails that previous errors must be able to be corrected by amendments to the constitution and the laws. Skepticism regarding the accumulation and concentration of power means that distribution of power is an important element of the liberal theory of government. Separation of governmental powers among different institutions, with each forming a check to the others, is one practical instantiation of this principle which serves as a safeguard to the freedom of the individual and a bulwark against government corruption. Democratic accountability in the form of representative, deliberative legislative bodies guards against the the tyranny of the few over the many. Constitutionally enumerated civil liberties, along with independent courts capable of striking down laws which violate them, guard against the tyranny of the many over the few.

Another notable feature of the liberal ethos is the open, pluralistic society. What binds a liberal society together is not base tribalism, or ethnic or religious nationalism, but a notion of civic virtue underpinned by a shared commitment to the principles previously enumerated. Liberal patriotism is a patriotism of ideals, capable of extending beyond the boundaries of race, religion, or national origin. Trade and immigration are not seen as threats to a nation’s greatness, but only serve to enhance the overall prosperity, knowledge, and cultural wealth of a nation.

One oft noted characteristic of liberalism is its generic or abstract character. Liberalism has been criticized on this basis as being sterile, cold, not respective of cultural distinctions and notions of group belonging, but I believe this generality in fact to be one of its greatest benefits. Liberalism at its root seeks to understand political freedom with respect to a notion of the individual, abstracted from all morally irrelevant particulars. This conceptualization is intentionally thin, meaning to capture the idea expressed above—that it is the sentient individual which is the seat of moral concern.

Liberalism intends to set out a framework for the freedoms of individuals purely in virtue of their moral status as sentient individuals such that, from these general conceptions, questions of freedom in more particular circumstances can be adjudicated. A woman’s right to terminate a pregnancy, for example, can be said to be a special case of the individual right to bodily autonomy. Not all individuals are women, or are capable of pregnancy, but all individuals have the same stake in bodily autonomy. Similar situations obtain for other rights. Defining liberalism in generic terms, in virtue of something all individuals share, allows liberalism its ethical universality and provides a unifying message that cuts across race, gender, sexuality, nationality, religion, and other such factors ancillary to one’s core nature as a sentient individual of moral value, and unrelated to one’s moral character.

This family of principles thus forms a certain framework through which particular policy questions can be answered, and a set of general premises upon which one can base public policy arguments. We can ask, does a proposed policy tend to enhance the freedoms and opportunities available to the individual citizen? Does a proposed structural government reform promote the sort of governance necessary to reliably and sustainably effect these ends?

Within this framework, the question of what sort of general freedoms apply to individuals as such is debated. One purported distinction which forms the basis of much of the debate is that between negative rights and positive rights. While there are various definitions available, negative rights can be understood as those rights which impose a negative duty on others, i.e. a duty to refrain from doing something, while positive rights are those which impose a positive duty on others, i.e. require something to be provided. Examples of the former are rights like the right to life or the freedom of expression, which require that others refrain from killing or censoring. Examples of the latter would be your right to an attorney or the right to healthcare, which require that the government provide counsel or healthcare for the indigent.

The distinction itself has been questioned both on theoretical and practical grounds, but it does help to illuminate a bifurcation within the liberal tradition between what could be termed its “right” and “left” wings. There are those who accept negative rights but who are skeptical of positive rights, often on the basis that the imposition of the taxes required for the state to provide these rights entails a weakening of the negative right to property. This group comprises various libertarian and fiscally-conservative-but-socially-liberal types. As one moves further leftward within the liberal tradition, more positive rights are included in the canon and property rights are not conceived as absolute, but amenable to exceptions in cases where other rights conflict. Most liberal democracies have in fact enshrined examples of both sorts into their constitutions or statutes, and the unconditional enforcement of many of the standard fare negative rights as a practical matter requires the provision of a system of courts, police, and lawyers—effectively a positive right.

There are as many positions as to the taxonomy of rights as there are liberal philosophers, none without objections. I do not intend here to provide such a comprehensive taxonomy, but to sketch a general framework, a manner of thinking that serves to approximate what I think to be a more promising understanding of individual rights. It begins not with an abstract notion of rights and duties, but with an understanding of freedom based on the first-person lived experience of individuals.

Freedom, from this perspective, is the real ability to choose those things which one values and to live the life one desires, not merely the absence of interference. In order for the freedom to do X to be of any tangible value in the lives of individuals, achieving X must be a real opportunity or power, or capability for that individual, otherwise one might well say that Tantalus is free to drink from the water whenever he likes, or that one is free to sprout wings and fly, provided no other individual or state power is preventing them from doing so. Interference from others can thwart an individual from achieving their desires, but so can structural or natural impediments. Little can be done about the latter, but structural socioeconomic impediments can in many cases ameliorated by political action. An attempt to understand freedoms as real capabilities has been undertaken by economist Amartya Sen and philosopher Martha Nussbaum, who provides a non-exhaustive list of candidate capabilities in her Creating Capabilities: The Human Development Approach, an interesting and worthwhile read for those interested in liberal theory. These understandings of freedom point us in a more leftward direction, seeking to liberate the individual not only from unfreedom imposed upon individuals by state power, but also from unfreedom imposed by private powers or by the consequences of poverty or other structural impediments to self-determination.

A system of political rights can be assessed on this basis by empirical means. Measuring things like freedom and well-being across nation-states is a necessarily imperfect science, but a nonetheless valuable one in which political scientists have made great progress. Various indices such as the Human Development Index, the Freedom in the World report, and others give us means of comparing political systems, and more targeted research into the individual conditions of well being give us better ideas as to what core human freedoms should be valued most highly as political ideals.

The process of refining our understanding of freedom and well-being is a deliberative human process, always imperfect and subject to error, which highlights the importance of the interacting liberal principles previously enumerated—the skepticism of power, deliberative, participatory legislative bodies, checks and balances and the rest. The process of liberal reform is sometimes gradual and imperfect, but tangible and durable over time.

This is precisely what we’ve seen through the history of liberal thought and reforms. To borrow an idea from Dr. King, the moral arc of liberal societies is long, but it bends toward freedom and justice. Once a society enshrines in its character and constitution liberal norms, it affords itself the levers by which generations of reformers to come will be able to effect change. America is a good case study in this phenomenon. Certain basic liberal ideals were enshrined in its constitution and founding philosophy: “Life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness,” “All men are created equal,” the freedoms of speech, religion, the press, assembly, and petition, the right to privacy, trial by jury, and other protections. Though these principles were not all implemented at the time of their adoption, and are not perfectly realized even now, they have formed the basis for the great reform movements that have defined successive generations of American life. Similar trends have been seen in other countries adopting liberal constitutions, from Western Europe to Asia.

It is a testament to the power of these core liberal ideas that the greatest liberatory reforms in our history have come about not by overturning these fundamental principles, but by recapitulating them, calling out the hypocrisy in the failure of government to live up to them, and taking them to their logical conclusions, thus enlarging their reach. It was thus that Frederick Douglass argued against slavery, excoriating the hypocrisy of a nation who would proclaim liberal principles of equality and liberty while allowing bondage and subjection within its borders. King did the same in the next century, saying:

All we say to America is, "Be true to what you said on paper." If I lived in China or even Russia, or any totalitarian country, maybe I could understand some of these illegal injunctions. Maybe I could understand the denial of certain basic First Amendment privileges, because they hadn't committed themselves to that over there. But somewhere I read of the freedom of assembly. Somewhere I read of the freedom of speech. Somewhere I read of the freedom of press. Somewhere I read that the greatness of America is the right to protest for rights.

Likewise Susan B. Anthony on women’s suffrage:

It was we, the people; not we, the white male citizens; nor yet we, the male citizens; but we, the whole people, who formed the Union. And we formed it, not to give the blessings of liberty, but to secure them; not to the half of ourselves and the half of our posterity, but to the whole people - women as well as men. And it is a downright mockery to talk to women of their enjoyment of the blessings of liberty while they are denied the use of the only means of securing them provided by this democratic-republican government - the ballot.

In the great progressive leaps forward of both the distant and recent past, from abolition to civil rights to the rights of women and LGBT individuals, we find appeals to liberal principles at the very heart of the rhetoric of these reform movements.

Though we have come far from where we started, we have many mountains yet to climb. A thoroughgoing liberalism along the lines expressed above can make the case for continuing radical changes to the status quo, including sweeping criminal justice reform, drug legalization, universal basic income, universal healthcare, humane immigration reforms, sex workers’ rights, death with dignity, as well as structural government reforms such as electoral system reforms, an end to the practice of gerrymandering, and more. The core principles of liberalism thus provide us with a map of unrealized and partially realized reforms, and a flexible but powerful blueprint for continual progress toward a freer, more just, and happier world.

Rethinking the Electoral College

The Electoral College has become a point of contention in the 2020 Democratic presidential primary debate, with several candidates calling for its repeal in favor of a national popular vote for the office of the presidency. This has spurred a renewed interest nationally in the Electoral College, its merits and demerits, and whether it should be scrapped, modified, or left alone. As one might expect, given recent electoral history, most of the support for repeal is coming primarily from Democrats and the left, with support for keeping the system as is coming from Republicans and the right. One might be tempted to write the whole disagreement off as bad-faith partisanship, but there are deeper philosophical questions at stake here, as well as conflicting interests that are not in themselves partisan. In order to decide this matter wisely as a nation, we must consider and evaluate the arguments adduced on both sides of the debate.

Note: Originally published by the author on The American Liberal blog.

The Electoral College has become a point of contention in the 2020 Democratic presidential primary debate, with several candidates calling for its repeal in favor of a national popular vote for the office of the presidency. This has spurred a renewed interest nationally in the Electoral College, its merits and demerits, and whether it should be scrapped, modified, or left alone. As one might expect, given recent electoral history, most of the support for repeal is coming primarily from Democrats and the left, with support for keeping the system as is coming from Republicans and the right. One might be tempted to write the whole disagreement off as bad-faith partisanship, but there are deeper philosophical questions at stake here, as well as conflicting interests that are not in themselves partisan. In order to decide this matter wisely as a nation, we must consider and evaluate the arguments adduced on both sides of the debate.

Before evaluating the various arguments for and against the Electoral College, it bears asking, “Just what is it?” One could write a treatise on its provenance and evolution throughout American history, but for the twin purposes of brevity and salience, we shall consider it primarily as currently constituted, with only brief mention of relevant historical factors.

The basic structure of the Electoral College is as follows: Each state is apportioned a number of electors equal to the combined number of representatives and senators from that state. How these spots are filled is determined by the laws of each respective state. These electors meet on a certain Monday in December following a November presidential election to vote for the offices of president and vice-president. It is their votes, rather than the national popular vote, which determines the outcome of a presidential election.

The founders originally intended that a state’s set of electors would be chosen by popular vote on a district by district basis. These electors would be non-partisan free-agents, who would meet and engage in a process of rational deliberation to select the most qualified and virtuous candidate. The people at large would not vote for presidential candidates directly, but would instead vote for these electors as intermediaries trusted to make a wise choice. This is manifestly not how the Electoral College functions today. The developments of distinct political parties, general ticket, and winner-take-all state rules have morphed it into something altogether different. As currently constituted, in 48 of the 50 states and DC, the people of a state vote for a presidential ticket, and the candidate winning the majority of the state’s popular vote receives all of the state’s electors. This is what is meant by statewide winner-take-all rules, and it makes the Electoral College effectively a weighted popular vote system, mediated through the states.

This system has many effects, but three are important to note here. One is that this system entails that individuals in the various states do not have equal voting power. Because the number of electors from a state is equal to its Congressional delegation, and each state has two senators and a minimum of one representative to the house regardless of population, an individual’s vote in a less populous state translates (assuming said individual votes for the winning candidate in that state) to a proportionally larger share of the effective electoral vote. The second consequence is that, due to the statewide winner-take-all rules, a good portion of voters in each state have no representation in the electoral vote count whatever. If 50.1% of a state’s voters vote for one candidate and 49.9% vote for a different candidate, the latter voting block will be unrepresented in the electoral vote tally. The third consequence is the fact that a candidate can lose the national popular vote, but win the Electoral College, and thus the presidency. This has happened four times in American history, in the elections of 1876, 1888, 2000, and 2016.

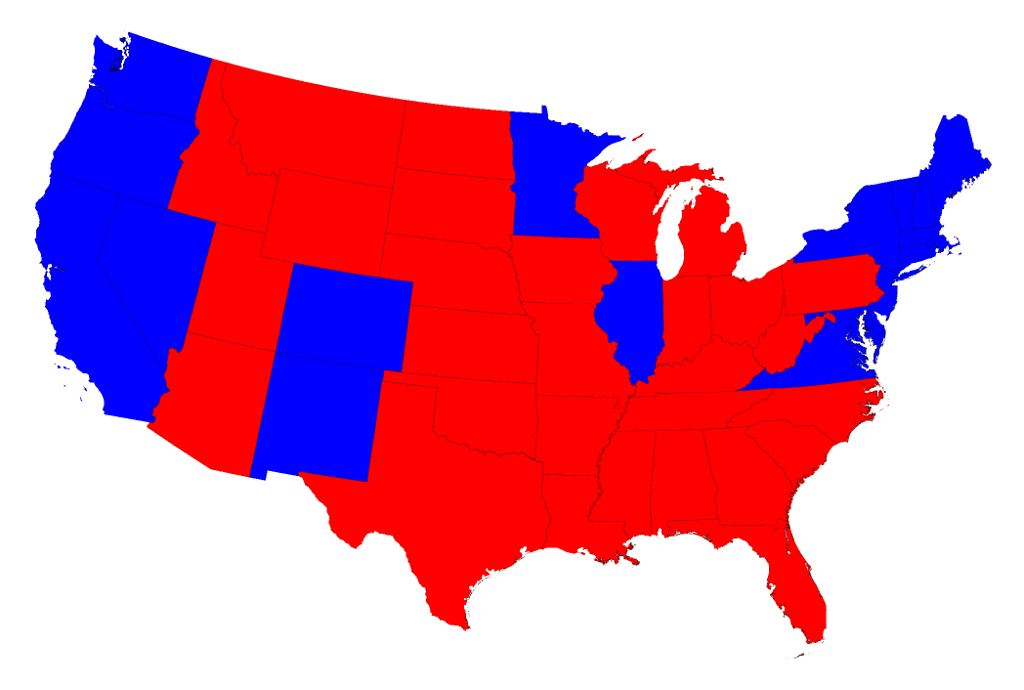

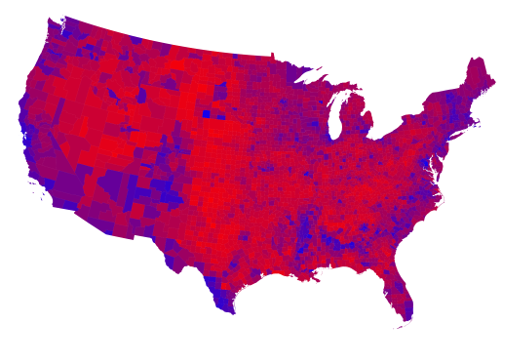

The statewide winner-take-all nature of the present system has the effect of skewing political perception and discourse, leading to talk of “red” and “blue” states and hiding the diversity of opinion within states, when each state is more realistically considered as some shade of purple. It also creates a situation where only a handful of competitive “swing states” are relevant to the outcome of an election. More on this later. To illustrate the effects of the winner-take-all system on the way we perceive the political alignment of the country, consider the contrast between the standard Electoral College map and the following one, which colors each county on a gradient between red and blue based on vote percentages within each:

One of the chief objections to the Electoral College is that it runs counter to the philosophical and legal principle of “one person one vote.” As mentioned, individual citizens in different states have unequal representation in the Electoral College, while those in minority voting blocks within each state are completely unrepresented. It violates two fundamental principles of democratic-republican government, representation and equality among citizens.

Another objection that may be levied against the Electoral College is that it does not actually answer to its original purpose and justification, and may in fact have effects contrary to the intentions underlying its initial conception. As originally conceived, the Electoral College’s deliberative process was to insulate the presidency from the whims of populism, preventing the election of an unqualified, incompetent, demagogic, or tyrannical individual to the highest office in the land. Many of the framers feared that popular election might lead to these outcomes, and so devised a system whereby these rational deliberators sit between the populace and the presidency. The current system, however, features no deliberative process, being a state-based popular vote, privileging voters in certain states more than others.

The foregoing fact is, interestingly, often adduced on both sides of the debate. As part of this critique, however, it leads us to the question of what kind of voters are disproportionately privileged by this weighting of different states. Rural, Southern states have electoral power which outstrips their population size. This comes as no surprise to the historian of American governance, who will remember that it was the Electoral College, as well as the Three-Fifths Compromise, which gave the slaveowning South its outsized political power. Slavery was abolished, Jim Crow defeated, but voting majorities in many of these more rural states are still privileged in the Electoral College over the majorities of many other states. One can wonder what effect this may have on the likelihood of electing someone the likes of whom the Electoral College is ostensibly intended to guard against. The though occurs that, if hedging against the tyranny of the majority is the object, perhaps a system that electorally privileges majorities in states which have long documented histories of popular majoritarian tyrannies against minorities might not be the best way to achieve that end.

Moving now to arguments in its favor, we must consider the flip side of this geographical privileging. Proponents of the Electoral College argue that instituting a national popular vote would lead to a situation in which candidates would be incentivized to campaign only in urban population centers, neglecting rural or less populous areas. As a consequence, the interests of these less densely populated areas would fall by the wayside. This concern is often bundled in with broader concerns about the role of federalism in the electoral system, and one sometimes hears this argument couched in talk about rural states vs. urban states’ interests.

First, as a response to this concern, it is not well established that a national popular vote would lead to candidates campaigning only in urban areas, given that it would incentivize generating as many votes as possible, and a sizeable portion of Americans live in rural areas. This concern is largely speculative. Second, we can observe that the current system already incentivizes campaigning only in a very small handful of swing-states, to the exclusion of all others, rural or urban. Whatever the effect a national popular vote may have on campaigning, it could hardly be as exclusionary as the current incentive structure.

Concerns regarding federalism underlie many of the defenses of the Electoral College system, so it’s worth discussing in more depth. Federalism, the distribution of powers between state and the federal governments, has been an integral feature in the makeup of our republic, alongside certain other features such as representative democracy, separation of powers among the tripartite branches, constitutionally enumerated rights, and the independence of the judiciary. Our government is a blend of different and sometimes contraposed elements, intended to distribute power and balance one another so as to protect the rights of individuals, and to promote the unity and longevity of our republic. One can think of the current debate in large part as one of the proper balance between the federalism element and the representative democracy element within our system of government. Both are important to consider, but which element is more relevant here, with respect to the relationship between the individual citizen and the presidency? Which element, in this context, tends more to protect the rights of individual citizens?

Important as it is, there are those who emphasize the role of federalism to a point such that they seemingly forget that it is a means to an end rather than an end in itself, and begin to talk in ways which are philosophically suspect. One hears talk of “states’ rights,” “states’ opinions,” and “states’ interests,” as if states were more than mere nominal objects. Without veering too far into metaphysics, we must note that states aren’t the kind of things that have the capacities of experience and thought, and thus the kind of things that can properly be considered to have rights or opinions or interests of their own accord. It is rather the individuals who live in a state who properly have such things as opinions, rights, and interests. Whatever talk about “interests of a state” means, it must ultimately reduce to interests of the individuals within the state in order to be coherent talk.

With that said, individuals within states do not vote as a single block, but are split percentage-wise. In so called “red states” there are significant “blue” minorities, and in “blue states,” significant “red” minorities. Under the current system, these minorities votes are electorally ineffectual. One must presume that these voters have just as much civic concern for the interests of other people in their states as do those voting with the majorities in those states. Interestingly, the same sort of concern that a rural minority might have its interests neglected in a national popular vote ought to apply equally to the voting minorities within these rural states who are completely voiceless under the current system.

Several factors are important to gleaning the proper relationship between the individual citizen and the presidency, and speak against the concern that a national popular vote would significantly differentially advantage the interests of some voters over others along state-wise divisions. One is that the primary areas of governance in which a president has greatest power to effect change are regarding issues of broad national or ideological concern rather than issues that bear upon voters’ state level interests. Two, whatever contribution one’s state of residency makes to his or her choice of president, one’s ideology makes a far larger contribution. Liberals in Alabama share more interests in common, in terms of electoral preference, with liberals in California, than they do with conservatives in Alabama. The same goes for conservatives in both states. So why be more concerned about the potential to unequally favor voter interests along geographical lines, which makes a relatively small contribution to their voting interests, than the real and current absolute disenfranchisement of vast swaths of voters along ideological lines, which make a far larger contribution to their voting interests?

At this point, the defender of the Electoral College has a rejoinder. The reason geographical interests should take precedence is to prevent regionalism among parties that could lead ultimately to the dissolution of the union. It is not an empty concern, though it is also arguable that regionalism is equally or more likely under the present system. There are regional paths to the presidency within the Electoral College system. Indeed, it is noteworthy that the secession of the southern states leading to the nation’s bloodiest war occurred under the Electoral College. Furthermore, as an empirical fact illustrated by the purple county map above, both major parties have ideological penetration across the nation, and partisan geographical differences are differences in degree rather than in kind. The concern about partisan regionalism seems far more well-placed in a pre-industrial, pre-information age than today, when cultural, social, and political groups are becoming more and more geographically decentralized.

So where does this discussion leave us? The considerations regarding lack of representation under the Electoral College as it currently exists, the disenfranchisement of large numbers of voters within states, the inequality of individual voters across states, and the swing-state phenomena which disincentivizes campaigning in much of America speaks to the need for reform. Worries about the role of federalism in preventing regionalism and urban domination, while not established empirically, are still legitimate concerns.

There are many ways one could go about reforming the Electoral College. Perhaps the simplest type of reform is to replace the Electoral College with a simple national popular vote. Several measures have been proposed for reforming the Electoral College, some requiring a constitutional amendment, and others (arguably) achievable through such means as interstate compacts. Proposals have been advanced in Congress introducing constitutional amendments to institute a national popular vote, but have all fallen short of the two-thirds majority in both houses of Congress needed to pass the amendment to the state legislatures for ratification.

A newer proposal, the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact, hopes to achieve the same end without the need of a constitutional amendment. In the compact, states would allocate all their electors to the candidate winning the national popular vote, rather than the statewide popular vote. To date, fifteen states and DC have signed on to the compact, making up 196 of the 270 needed to win a presidential election. The compact is written so as to go into effect only after enough states have joined to make 270 votes, thereby turning the country into a de facto national popular vote system. Notably, this proposal implements a national popular vote while retaining the framework of the Electoral College, by using the plenary power granted to the states by Article 2, Section 1 of the U.S. Constitution to choose the manner in which electors are appointed. The compact is likely to face legal challenges under the constitution’s Compact Clause requiring Congressional consent for states to enter into agreements and compacts with each other, but it may nonetheless be more easily achieved than a constitutional amendment.

Aside from instituting a simple national popular vote, numerous other possibilities are conceivable. One such possibility involves states allocating electors by districts, either by Congressional Districts or specialized Electoral Districts. The primary impediment to this sort of reform is partisan gerrymandering, which has just been upheld by the Supreme Court. Without Congressional action to ban gerrymandering, any gains in representation would likely be offset by these gerrymandered districts. Partisan gerrymandering would also likely become even worse by joining it to presidential politics. A simpler, fairer system along similar lines is to have states allocate electors proportionally to the various candidates, according to the statewide vote, based on a uniform mathematical formula. Both of these ideas seek to make the Electoral College more representative of the voters within states, eliminating statewide winner-take-all, and thus removing the disenfranchisement of minority voting blocks within states. Unlike the national popular vote, however, they do not go so far as to make all voters equal in voting power. It can be seen as a compromise between those concerned with the one-person-one-vote principle and those concerned with the urban-rural balance of power, as it still retains the current allocation of a number of electors per state which is not directly proportional to each respective state’s population.

Another interesting idea which would enfranchise all voters, institute one-person-one-vote, and also protect against regionalism is to institute a national popular vote with certain conditions. One could stipulate that to win a candidate must win the national popular vote as well as the statewide popular vote in a minimum number of states, or have a minimum percentage support in a certain number of states. The details would have to be fleshed out, but in principle, such a system would possess most of the best features of both the national popular vote and the current system.

No reform is likely to please everyone, and none will be free of negative as well as positive consequences, but one must weigh these consequences and decide which sort of reform stands to best achieve the ends we desire as citizens, that is, to further our individual liberties, make our system more representative, and foster the long-term stability of the republic.